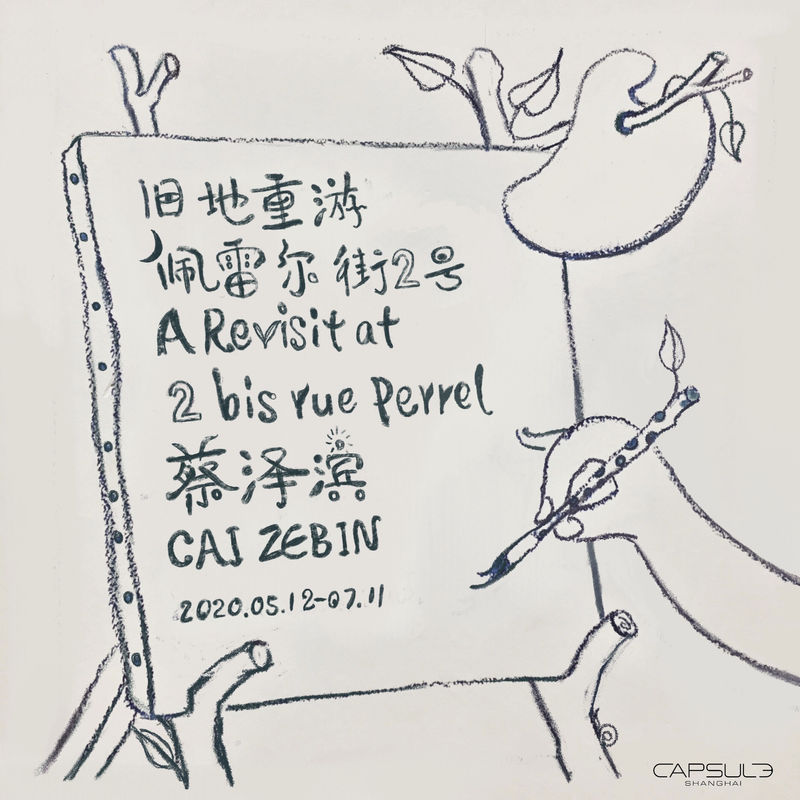

Capsule Shanghai is delighted to present artist Cai Zebin’s second solo exhibition, “A Revisit at 2 bis rue Perrel” at the gallery. Consisting of the artist's most recent paintings, small drawings, and installations, that extend from the artist’s continuous fascination with the relationship between the symbolic, the imaginary, and the real in creativity.

The title of this exhibition, “A Revisit at 2 bis rue Perrel” draws from Victor Brauner’s (1903-1966) eponymous painting whose work paid tribute to Henri Rousseau while living in his former residence. In Brauner’s painting, not only do we find the artist’s appropriation of Rousseau’s famous work, The Snake Charmer (1907), but also a surrealist icon of many limbs that be known as uniquely his. Hence, Cai’s adoption of this title demonstrates the artist’s intention to reveal the genealogy of images and visual resources that inform his practice, as well as asserting his position to this approach for creativity. “How does a work of art come into being?” – a question driving Cai’s painting practice as much as the viewer standing in front of his works of art.

To resonate with the intent Cai Zebin has laid out in the exhibition’s title, Revisit (2019), one of the large-dimensional paintings in this exhibition, conjures many visual elements that complicate our possible interpretation of this work on canvas. The three central figures draped in black from head to toe, each holding a red ball in one hand while having their mouths wide open. To those viewers who are informed in visual culture, these three figures have been iconic over the centuries. They may immediately recall many classics in art history ranging from Antonio Canova’s Neo-Classical sculpture, The Three Graces, to Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera, to Raphael’s Three Graces from the Renaissance, to even Andre Derain’s The Dancer in the post-impressionist period. At the same time, what's once depicted as nudes throughout the history of art is now draped in black latex wetsuit, what conveyed peace and serenity is now replaced with a sense of awe. As the disco lights in red beaming at them from all directions, the stage on which they stand begins to resemble a scene in Andrzej Zulawski’s film, My Nights Are More Beautiful Than Your Days (1989). Furthermore, the area off stage and the high-rises on the back seem like two different spatial dimensions. What do each and the sum of the visual cues suggest and how should one understand a painting as such become the questions Cai Zebin presents to the viewer.

In fact, this approach to painting is very much in line with the central piece Invitation to a Beheading presented in his previous exhibition at the gallery. Cai appropriated Theodor Gericault’s masterpiece, The Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819), by adopting a literary device, the narrative of Vladimir Nabokov’s novel The Defense. For this exhibition, however, the scope of the artist’s visual resources expands to include a broader spectrum of visual culture, ranging from the classical paintings to pop cultural icons of the present. Furthering what Henri Rousseau stated in the early 20th Century on taking nature as his realm of inspiration. For Cai Zebin, "Imagination is the sum of all my visual experiences from reality” written on a small painting among the many revealed to his viewers. This statement is also considered a prism to the condition of artistic practice today. How does one translate and transfigure all of these visual resources available on to the canvas?

In one of the exhibition spaces, Cai Zebin lays out many of the small drawings he had done in the course of creating the large-dimensional pieces for this exhibition. They comprise of head-portraits of Henri Rousseau, the "premature" drawings of Three Graces, the flute player in black in Henri Rousseau’s The Snake Charmer (1879), biblical icons of the serpent and the apple, snow white and the witch tempting her with the poisonous apple and etc. It is their metamorphosis that sheds light on the mind of the artist. Of course, each visual cue embedded with many layers of meanings, as well as their evolution from the context in which they first emerged, influences how we perceive them today. Hence, their coming together on canvas opens up the potential for their reception now. Moreover, the palette-shape mirror, the most subtle yet pivotal device in this exhibition, not only references to the one in Henri Rousseau holds in his self-portrait in front of the Eiffel Tower but also projects what Jacque Lacan defines the functions of the mirror for bringing together the real, the symbolic and the imaginary. In other words, our reflection in the mirror, as artist and viewer, continues to relay as we explore the evolution of creativity with the understanding of the context in which we inhabit.

Text: Fiona He